From the cult favorite Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which netted four million viewers per episode, to the summer blockbuster The Avengers, which amassed a box office of $1.5 billion, Joss Whedon has made a name for himself in Hollywood for his penchant for telling meaningful, personal tales about love, death, and redemption even against the most dramatic and larger-than-life backdrops.

Extensive, original interviews with Whedon’s family, friends, collaborators, and stars—and with the man himself—offer candid, behind-the-scenes accounts of the making of ground-breaking series such as Buffy, Angel, Firefly, and Dollhouse, as well as new stories about his work with Pixar writers and animators during the creation of Toy Story. Most importantly, however, these conversations present an intimate and revealing portrait of a man whose creativity and storytelling ability have manifested themselves in comics, online media, television, and film.

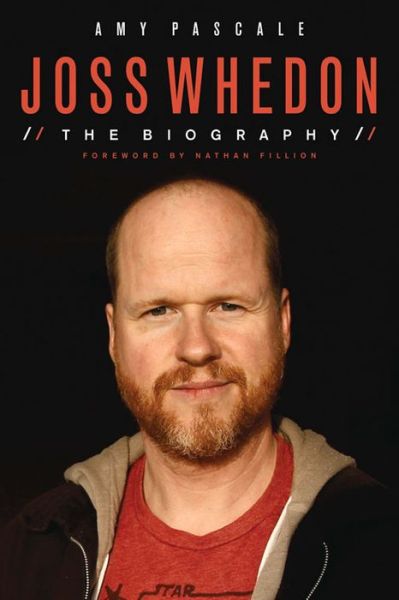

Amy Pascale’s Joss Whedon: The Biography is available now from Chicago Review Press!

Chapter 18

Curse Your Sudden but Inevitable Cancellation

On paper, the fall of 2002 was to be a banner television season for Joss Whedon. With Buffy on UPN, Angel on the WB, and Firefly starting up on Fox, he would have three series on as many networks. And his success wasn’t limited to TV. On Tuesday, September 24, the same day as Buffy’s seventh season premiere, Joss Whedon released a CD.

The Once More, with Feeling soundtrack album, from the independent music label Rounder Records, included all fourteen original songs from the Buffy musical. Although Joss had closely overseen every creative element of the musical, he left the marketing in the hands of new Mutant Enemy head Chris Buchanan. “My marching orders [from Joss] when I got to the company, literally the first day, were ‘I want to be able to go to Tower Records and have the original cast recording CD there,’” Buchanan says. When he started to ask about the musical rights, Joss reiterated that he was just concerned with Tower Records stocking the CD. The rest was up to Buchanan. “That was great; I think that made for a good partnership, because that’s what I took care of.

“Think about it—that’s from somebody who’s an incredible micromanager on the creative side. On the business side, he wasn’t at all, because he didn’t care about that. That gives me a tremendous amount of flexibility in accomplishing the goal, and it was a really hard process to do it, but I remember being able to say, ‘Hey, dude. Go to Tower Records. Your CD is on the shelf and it’s really good.’” Once More, with Feeling would sell 150,000 copies in the United States by December 2004—an impressive number for a soundtrack from a “cult” show. In the United Kingdom, Buffy merchandise had already been selling particularly well,as DVD and VHS box sets were the only (legal) way for British fans to watch the series without dealing with the erratic scheduling and censorship of local broadcasters, but even so, everyone was surprised at how well the album sold internationally, especially in the United Kingdom and Germany.

“Once More, with Feeling” would go on to another life off the small screen. Taking a cue from The Rocky Horror Picture Show, fans began staging public screenings of the musical, where they could dress up like their favorite characters, sing along to the musical numbers, and shout out sardonic commentary. By 2007, it would become such an event that Marti Noxon and Joss attended a sing-along at the Los Angeles Film Festival. However, in October of that year, after 20th Century Fox received a bill from the Screen Actors Guild for unpaid residuals from the screenings, the studio pulled the licensing, putting an end to the events. Joss called the move “hugely depressing” and promised to do anything in his power to convince the studio to reconsider. “Of course,” he added, “the words ‘my power’ might confuse my gentle readers into believing I have any.”

In lamenting his powerlessness, Joss was perhaps recalling an earlier conflict with Fox’s broadcast arm, which led to the swift unraveling of one of his three TV projects for 2002. Joss’s struggles to keep Firefly flying are legendary among Whedon fans, and they all came down to one central problem: the Fox network didn’t get the series that it was expecting—a pithy Buffy-esque action series set in space—and didn’t know what to do with the series it actually got.

The first warning signs came in May, when the network was putting together its 2002–03 schedule for its “upfront” presentation, the annual meeting at which a network previews its fall schedule for advertisers. Fox was about to lose two of its flagship series, Ally McBeal and The X Files, and it had two sci-fi shows on tap to fill the void left by the latter. A few days before the upfront, there was talk that the other series, the James Cameron–produced Dark Angel, would be renewed for a third season and placed on the fall schedule, while newcomer Firefly would be held until 2003 as a midseason replacement. But by the time of the Fox upfront on May 16, Joss’s series had been added to the fall roster and Dark Angel had been canceled.

With the good news came some more bad news. Gail Berman had scheduled Firefly in what is often referred to as the “Friday-night death slot.” Series often have a hard time attracting an audience in a Friday time slot, most likely because that’s when the coveted demographic of viewers ages eighteen to thirty-four are going out to start their weekend. Ominously, it’s the very slot into which Dark Angel was moved prior to its cancellation.

What’s more, before it could even premiere, Firefly needed a new first episode. Berman did not like what Joss had delivered in his two-hour pilot, “Serenity.” Fox executives outlined a list of reasons why they felt that it didn’t work, including that it was too dark and not filled with enough action to keep a younger audience engaged. Their complaints frustrated Joss, who had made the show he wanted to make—a story about people living on the edge and the small moments that make their lives meaningful. For him, the most important scene in the whole pilot was the one in which Kaylee is alone eating a fresh strawberry, a rare treat for those always on the move in a spaceship. “That’s what we do in our homes—we’re creating our lives, our ethics,” Joss said. “Whether or not we have a template or someone gives us money, everything we create, we do ourselves.” Firefly, he added, “is about these quiet moments in between the gun battles.”

Still, Joss did reshoots to address every one of the network’s doubts as best he could. To grab young viewers with action, he shot an opening war scene. To make sure the main character didn’t come across as too grim, he put in scenes in which Mal displayed a sense of humor. Fox remained unsatisfied. The network asked him to produce another episode with which to introduce the series—one that was less “Stagecoach in space” and more like an action-oriented futuristic spin on Sam Peckinpah’s violent 1969 western The Wild Bunch.

Joss and Tim Minear had two days to write a new premiere script. It needed to do all the heavy lifting of introducing the characters and setting up their situation that had already been done in the pilot, while also presenting a new, more action-packed story. They scrambled and produced “The Train Job”—which, compared to the original pilot, does provide a smoother welcome for those coming to the series through their love for Buffy and Angel. The episode immediately sets up Mal’s tendency to walk willingly into a fight when he could avoid it, Zoe’s unwavering support for her captain even when she knows he’s being stupid, and the fact that our heroes will take as many hits as they dish out. By the end, it’s clear that while this crew of smugglers is not happy getting by with very little, its members will risk crossing a sociopath and losing out on a bounty in order to return needed medicine to those stuck in a situation far worse than their own.

The concessions the writers made in their “Train Job” script were early examples of the constant tug-of-war about the “darkness” of the show. Joss didn’t want everyone drawing their guns in every episode, and he certainly didn’t want Mal to be killing people indiscriminately. But he got notes that Mal needed to kill more people. “This is something that was problematic,” Joss says. “[Fox’s] insistence that it be less dark made it, on some level, more offensive. I wanted Mal to have to make really horrible decisions that were tough and that he would have to live with.” Fox instead said that they would like for Mal to shoot a guy and make a joke. So at the end of “The Train Job,” Joss had the captain kick a guy into the ship’s engine. As Joss puts it, “It’s hilarious! I just compromised my morality. Woo-hoo!”

He adds, “They tried to strangle it when it was in the womb. You forget, [creating a television show] is like childbirth. ‘Sure, I’ll squeeze another one of those things out! It doesn’t hurt, right?’ Well, of course, it does. None of them have been easy.”

In truth, Firefly was much darker in Joss’s imagination than it would end up being on screen. One of his first pitches, which he gave to Minear as he wooed him away from Angel to be Firefly’s executive producer, would never see the light of day. Joss explained that as a Companion, Inara has a special syringe. She injects herself before meeting a client, so that if she is raped, the rapist will die a horrible death. In this story, Inara is kidnapped by the savage Reavers. When Mal finally reaches the Reavers’ ship to save her, he finds them all dead. At the end of the episode, after she’s been horribly brutalized, Mal gets down on his knee and takes Inara’s hand, treating her with the respect of an esteemed lady (which he was usually reluctant to give her) as he takes her home to Serenity.

“It was very dark,” Minear remembered. “[Joss] said, ‘These are the kind of stories we’re going to tell.’” But as they had learned with Angel, they couldn’t start the series out with such grim and gritty tales without earning it.

Firefly’s troubles didn’t end when the series finally made it to air. Episodes almost immediately began to be preempted by Fox’s coverage of the Major League Baseball playoffs. Then Fox started airing the episodes out of order, disrupting the character and story arcs that Joss and Minear had carefully planned out. But one of the biggest ways Fox mishandled the series was how it chose to market the show.

Instead of advertising Firefly as a space western or a gritty sci-fi show, the promotional campaign suggested that it was a wacky genre comedy—“the most twisted new show on television.” Several promos strung together jokes about a “flighty pilot” (Wash), a “space cowboy” (Mal), a “cosmic hooker” (Inara), and a “girl in a box” (River, referencing a plot point from the pilot episode the network refused to air), tied together with the tagline “Out there? Oh, it’s out there!” Another reduced the show’s complex premise to a tired cliché about a “band of renegades” for whom “the only thing that mattered was profit until they discovered something worth fighting for.” Much like the directors whom Joss had resented for mishandling his feature film scripts, Fox marketing was twisting Joss’s vision to fit their own, promoting Firefly as the Kuzuis’ campy version of Buffy the Vampire Slayer if it were inhabited by the poorly realized mercenaries from Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Alien: Resurrection.

“We knew we were in real trouble before the show debuted,” Chris Buchanan says. Fox sent them a promo reel of the spots they’d cut for the show, and the first opened with Smashmouth’s hit song “Walkin’ on the Sun.” They first thought that the promo was for Fastlane, Fox’s highly stylized police action drama. “Then all of a sudden it was like ‘Firefly, the cosmic hooker and a whacked out space cowboy.’” Buchanan recalls, horrified. “My mouth just dropped open. When the marketing guy called back to ask what they thought, I said, ‘Well, it’s really great, but that’s not what our show is.’ I don’t remember exactly what he said to me, but it was along the lines of ‘Our job is just to get people to watch it, and then they’ll figure out what it is, and they’ll stay.’” Buchanan replied, “So you’re selling them this goofy comedy thing, and then they’re gonna get Firefly.”

Sure, there’s funny in Firefly, but it’s not a wacky space comedy. (Just as Buffy wasn’t a wacky horror comedy either; in its attempt to appeal to Buffy viewers, Fox had misunderstood that show as well.) While Joss’s fans were excited and ready to turn out for the premiere, the promos were so off base that anyone else who might have been interested in what the show actually had to offer was turned off, while those who liked the show that Fox was promoting would be greatly disappointed by the real thing.

At times, Joss’s new show seemed to be considered the bastard stepchild even within Mutant Enemy. While his other two productions were successful, long-running series, Firefly was the little show that couldn’t. And yet “we got the best people from those other two shows,” Nathan Fillion recalls—something the people on those shows didn’t always appreciate. “They’re looking at us going, ‘What’s happening? What’s Firefly got that we don’t got? You’re taking our best guy? C’mon!’ ”

As the other Mutant Enemy casts may have suspected, Firefly had quickly found a special place in Joss’s heart. He was passionate about the universe he’d created and—even though he’d impressed upon the actors that they were all replaceable—about the cast he’d assembled. “I never worked with an ensemble that meshed like that,” he recalled. He’d never felt so sure right from the pilot how a show was going to work. “It was Camelot. It was the best experience of my career.”

His actors were just as enamored with the experience. “I’ve always pulled at least one friend out of everything I’ve done. With Firefly, I think I pulled about thirty-five friends out of that thing,” Fillion says. “Not just cast, but writers and producers and crew. People I still call and people I still chat with. People I still hang out with,” Fillion says. “Joss did this great job of saying, ‘You’re going to be great at interpreting these words and you’re going to be great to have around.’ I made so many good friends. That was ten years ago and I’m still close to these people. I still love these people.”

The feelings of cast and crew are perfectly embodied in the episode “Out of Gas,” which aired on Fox on October 25, 2002. It was a “bottle episode,” filmed entirely on existing sets to spare the show the time and expense of location shoots. The plot is simple: Serenity has stalled in space and is running out of oxygen thanks to a broken part, compelling the crew to abandon ship. As the captain, Mal stays behind to meet another group of smugglers, purchase a new part, and make the repair. Wash sets a red recall button on the ship’s helm, instructing Mal to press it when it is safe for the crew to return. Unfortunately, Mal gets shot and almost bleeds out before he can hit the button. His crewmates return anyway, coming back home to their captain.

Written by Tim Minear, “Out of Gas” is Firefly’s origin tale, with flashbacks that explain how each person came to be part of the Serenity crew. The last image of the episode is the moment when Mal sees Serenity for the first time. That moment is shot with all the love-struck anticipation of “seeing this beautiful woman across a crowded room,” Minear said. “That was Joss and us saying, ‘We fell in love with this thing too.’ There was already a sense that it was slipping away from us at that point. And the sense of that is in that episode.”

In November 2002, Fox buoyed hope for the series by ordering two more scripts into production. Four days later, the network preempted the show yet again, this time for an Adam Sandler movie. It was clear that the series was in a precarious position. Its creators reached out to their online fans for help.

If you watch just about any show on television today, you’ll see an ad with a Twitter hashtag encouraging fans to discuss the episode they just watched online. It’s strange to think that just a decade ago, Mutant Enemy’s Chris Buchanan had to struggle with Fox’s marketing department to shore up Firefly’s online presence. “I went to Fox very early on in the process and said, ‘What’s going on with the Internet? We need to get the site up—it’s got to be multimedia, and we need a lot of video.’” Fox felt that he was jumping too far ahead too quickly, considering the series hadn’t even premiered yet, but Buchanan pushed back, asking why they would wait.

“USA Today did an article about Internet and television, like how influential the Internet was for TV,” he remembers. “I was quoted saying something like, ‘I actually think that the Internet communities are going to be able to make or break a show.’ They kind of hung me out there like the optimist of ‘This Internet thing’s gonna work.’ Fox, to their credit, said, ‘OK, if you want to. Yeah, great, knock yourself out. Go and get this thing rolling.’ They let us put a lot of video and stuff up before the show aired, which was not done at the time.”

The official message board was poorly designed and wasn’t terribly user-friendly, but it quickly became a central location for people to express their love for the series, pore over the episodes, and discuss the characters. Another common topic: the ratings. In recent years,television viewers had become savvier, checking the Nielsen ratings aftereach airing to see how their favorite shows were faring. For Firefly, itwasn’t looking good.

Another place to follow all things Firefly was the new fan site Whedonesque.com, a sort of clearinghouse where people could share news and updates about anything Joss Whedon–related. Caroline van Oosten de Boer and Milo Vermeulen had launched the site in June, and it quickly became a source of breaking Joss news, CNN style. The simple text site linked to articles and videos about Joss’s projects new and old, as well as projects from other Whedonverse writers, actors, and crew. Once someone was in a Mutant Enemy project, he or she was brought into the fold and soon learned that acceptance came with a passionate and supportive fan base. “Without Whedonesque, Joss wouldn’t even know what was going on in his own life,” Kai says. “He goes there to find out what’s going on with his friends. Whedonesque is like his Day-Timer [appointment book].” For Firefly fans, Whedonesque was the place to read everything from cast interviews to ratings breakdowns to the latest on the fan movement to “save” the show.

By November, several cast members were posting messages directly to fans on the official Firefly site, while Kai reached out to the webmaster at another fan site, JossWhedon.net, asking for help in getting the word out about the show. Soon after, a fan-led campaign called “Firefly: Immediate Assistance” mobilized, and an army of fans calling themselves Browncoats after the show’s rebel resistance organized to plead for Firefly’s continuation. They sent postcards to news outlets asking journalists to cover Firefly in their columns, raised funds for the placement of a full-page ad in Variety, and organized viewing parties throughout the United States. Mutant Enemy kept in touch with the fan organizers and even provided the hosts of viewing parties with publicity photos and a copy of Nathan Fillion’s recipe for seven-layer bean dip.

On December 9, the Variety ad ran, featuring the headline You Keep Flying, We’ll Keep Watching. Joss posted his thanks on the fan site Buffistas.org:

I’m only posty for a moment to say… (starts to cry…) I promised myself I wouldn’t cry… That Variety ad… I have the coolest fans ever. So classy, so passionate (the ad AND the fans), I must be doing something right. Or paying Tim to do something right.

Unfortunately, despite the passion of the series’ creators and fans, the campaign hadn’t convinced many other viewers to tune in to Fox on Friday night. By mid-December 2002, Firefly was averaging 4.7 million viewers per episode—more than even the highest-rated episodes of Buffy and Angel but a dud by Fox standards at the time; the series was expected to pull in almost triple that amount. With three of its fourteen episodes still unaired and two of them still in production, Firefly was canceled.

The official news of the cancellation came on Thursday, December 12, 2002, while they were filming the episode “The Message.” In it, a former soldier (Jonathan Woodward) who served with Mal and Zoe in the war with the Alliance has his corpse sent to them with the request that they bring him home. The taped message that he includes with his body recalls an oft-quoted mantra of their unit but breaks off early: “When you can’t run anymore, you crawl, and when you can’t do that…” Mal and Zoe silently acknowledge the missing ending to the line and, always loyal to their men, decide to honor his request.

“We were on the bridge shooting,” Tim Minear says, “and Joss showed up on the set and he pulled me aside and he’s like, ‘They just canceled the show.’” Joss then asked if he should announce it while everyone was gathered or wait until shooting was done. Minear said to tell them immediately and they’d all wrap for the day.

“I’ve never seen him so mad,” Adam Baldwin recalls. “He looked at me and said, ‘I don’t have good news. They pulled the plug and this is the last episode. And I wanted you all to know immediately.’” After Joss informed his cast and crew, nobody felt like working, so they all went to Fillion’s house to get drunk and drown their broken hearts.

“It was right before we were going to break for hiatus and go home to our families for the holidays,” Jewel Staite recalls. “We all had a good feeling that we were the underdog that year, but it always felt like our impending cancellation was just looming over our heads, and I think we were all waiting for some sort of shoe to drop. It was still devastating, though. Kind of like when you jump off a diving board, and instead of going headfirst in the pool, you twist your body the wrong way and hit the water with your belly instead. It felt like that.”

But they still had to finish production on the remaining episodes. The next day everybody was hung over, and the first thing they had toshoot was a scene in which Mal, Zoe, and Inara sit around the diningroom table laughing hysterically as Mal tells funny war stories about theircomrade. “We’ve just been canceled and they have to pretend like they’rehaving a laugh,” Minear remembers. Ultimately, Joss and his cast andcrew decided that joking around was exactly what the situation calledfor. They were going to have the best time they possibly could have, andthen it would be over. “We would screw things up, you know—like, notget something right—and the joke was always ‘What are they gonna do,cancel us?’” says Morena Baccarin.

Baccarin also recalls how during the later days of filming, Joss helped her reach a deeper emotional truth and find an emotional release. In “Heart of Gold,” Inara tells Mal that she will be leaving Serenity. “I understood how that scene was really sad, and I did it a few different ways. Joss said, ‘That’s really, really good and we have those takes, but now try one where you have to put on your best face and you have to pretend that you don’t give a shit that you’re leaving, because if you show him that you care, he’s going to convince you to stay.’ That brought a whole other layer to that scene—it made me sadder, it made me have to fight harder against showing that, which in turn made me cry,” she says. “You know, it was like the oldest trick in the book, you know—don’t cry, and you cry. But it was such a great piece of advice.”

On the last day of shooting, the cast and crew had to finish scenes for both “The Message” and “Heart of Gold.” When filming an episode of a TV series, on the last day of a guest star’s shoot, the assistant director will announce that it’s “a wrap” for the guest star. Everyone will clap, and the guest star will thank everyone and go home. Ordinarily, the regular cast members don’t get such a send-off, since they’ll be back the next week. But on this day, there was nothing to come back to. So every time an actor shot his or her last scene, the assistant director declared, “That’s a Firefly wrap” for him or her. The rest of the cast and crew applauded, the actor gave a sad speech, and then it was onto the next scene. But no one left when they were done. They all waited for the others to be finished, because, like on Serenity, the cast and crew of Firefly had become a family.

At the end of the day, Tim Minear headed home, emotionally exhausted. “It’s Friday. The show is finished. They are now tearing down the spaceship,” he recollects. “I get home, turn on the TV, and what’s on TV? The pilot. They’re finally airing ‘Serenity.’”

The spaceship was being torn down, but bonds of its crew were stronger than ever. Many cast members talked about the fact that not only was Mal the captain of Serenity, but Nathan Fillion was also like the captain of the cast. They called out his wonderful disposition and how well he worked with everyone, and said that they looked to him as a leader behind the scenes as much as on camera.

“God bless them for that,” Fillion demurs. “I don’t know how much responsibility I can take for that; I don’t know how much credit I can take for that. I was grateful to be there—not only to have a job, I had to tell the story I was telling. I was thankful for each and every one of them. I was surrounded by talented, wonderful people. What could you be except happy?

“They’ve said these things about me being a leader. I say, they carried me. I didn’t have to do the work to be a captain, because when I walked around, they treated me like the captain. I was on a spaceship, dressed like a space cowboy walking around. Everybody had their own attitude toward me and authority itself. I didn’t have to do any work. I just had to listen, I just had to watch them. I just had to be there. It’s funny how our perspectives are different. I didn’t feel like the leader. That’s actually another thing that my adventures with Joss Whedon have taught me: pick the right coattails to ride. There are some amazing, incredibly talented people who are kind and generous. Grab ’em! Grab ’em.”

The Firefly cancellation hit Joss hard. “I promised these [actors] that if this was good it would go,” he later said. He kept telling the cast that it wasn’t over, that he would take the show somewhere else. “I went crazy; I would not accept cancellation,” he said. He had a production deal with Fox and got together with Minear, agent Chris Harbert, and his lawyer in hopes of finding a way to continue the story. “Joss was so dedicated to the show,” Adam Baldwin recalls, “and so heartbroken, as we all were, that when it went down he was going to try to keep some of the sets, and put them up in a warehouse and keep filming on his own. That just wasn’t in the cards. But he kept fighting.” The cast was sad that Joss seemed to be in so much denial. “I love him,” Baccarin says, “but I waslike, ‘This show is gone. Nobody wants it. It’s dead.’”

As his series ended, another story in Joss’s life was just starting. Five days after Fox announced that the show had been canceled and two days before it finally aired the pilot, Kai gave birth to their son, Arden, on December 18, 2002.

Though it was a new beginning for Joss, it was perhaps not quite an ending for Firefly. After the series was canceled, actor Alan Tudyk took an item from the set: the recall button from the episode “Out of Gas.” In the spirit of the crew and their love for their captain, he sent it to Joss, with the instruction to hit the button when his miracle finally arrived.

Joss Whedon: The Biography © Amy Pascale 2014

Thank you so much for that particular excerpt. Now I’m pissed of all over again. It’s been 12 years and I still pop a vein every time Firefly’s cancellation is mentioned.

Where’s the booze and my blankie…?

I HATE HATE HATE that Inara story.

Not that it’s not a good story, I just HATE that getting raped is the thing that FINALLY gets Mal to treat her with respect.

Among the many things wrong with Firefly, and particularly the Inara and Kaylee arcs — this inability to think outside the cliche / stereotype of what female characters do and thinks and say. Just as a concept, the whore with a heart of gold is bs.

Well Mal has always respected Inara, he just hides it behind this facade of disrespect. I think perhaps that scene is meant to illustrate that.

@@.-@, I know that. But a person shouldn’t have to be raped, to be treated as worthy of outward respect.

It just confirmed all the worst parts of Mal’s character to me, and I hate that this attitude is what epitomizes his wonderfulness to people like Minear(who I am not a fan of anyways)

I’m not an impulse buyer by any means. Nevertheless, I logged onto Amazon.com the minute I finished reading this excerpt. Eagerly awaiting this book’s arrival at my home.

I never watched Firefly, and after reading this cancellation story and how brutal it was for everyone involved, I feel the need to finally check it out (plus, the Sonny Rhodes ballad is brilliant).

#5 I don’t get that vibe at all. Sure, we are meant to think he treats her disrespectfully in the beginning, but at the end of the arc, after Heart of Gold, Shindig and Out of Gas, we all know that this is just part of a two way pissing contest between two really close people. And Inara knows that from the first episode, as shown by her speach to Booke and her ultimatum to Mal over River and Simon.

And if you think Mal cannot treat a lady with respect, just look at the particular trope episode, Heart of Gold.

As for whether the hypothetic needle arc would have been exploitative or clicheed, that is another question, but I choose to believe this crew and cast would have made it good. Dark and maybe revolting, sure, but heartrending at the same time.

Actually, it doesn’t say he treated her with respect, it says he finally treated her with the “respect of an esteemed lady”… which implies a certain level of chivalry. Which, as I have so often been told on this site, is a certain, irredeemable sign of chauvanism. So it seems by that definition, Mal would be doing something anti-feminist toward Inara by treating her with the “respect of an esteemed lady.”

Its also worth pointing out that Minear was relaying a plot that Joss had developed, not himself.

@8, That’s Minear’s story, I heard him talk about it at the Browncoats Unite roundtable they recorded right before the reunion panel at SDCC.

The idea that she had this drug was Joss’ idea, but the whole “Inara is brutally raped and uses that to kill Reavers, and Mal is respectful towards her because of it” was Minear. He elaborates that Mal would have knelt before her, very chivalric like.

It just rubbed me the wrong way. It’s not that I don’t think the story should have been done, I too am sure with this cast they could have sold it. Just the idea that Mal was going to totally switch his behavior, and THAT’S the reason just ticks me off.

His behavior is Heart of Gold just goes to show you how terrible Mal is when it comes to this. A woman prostituting herself to poor people, THAT’S OK, but a woman like Inara who prefers the security of a higher class clientele, well she deserves all the disrespect he can give her.

And the fact that Inara is willing to look past his boorish behavior and see the truth of the man beneath, doesn’t excuse his behavior. Women, especillay women like Inara who are engaged in work that is looked down upon, are used to having to excuse the terrible sexist behavior of the men they care about, it still doesn’t make the behavior acceptable.

Looking at this summary of the needle plot I can’t see a way it wouldn’t have been offensive regardless of Mal’s reaction. You have the white woman being kidnapped by savages to sate their lusts. Lusts that are apparently so powerful they’ll keep raping even after they start to drop dead. More than a little problematic since “Firefly” is a Western with the Reavers filling the space of Native Americans. And how does our brave female character fight back against her attackers, by lying back and thinking of England. Establishing that all of the character’s power is grounded in sex. Since summary implies that the drug can detect rape there are odds on reinforcing the BS idea of “legitimate rape” also.

–

Overall this excerpt reads like a puff piece that is mainly concerned with staying on the subject’s good side. It lacks meat and only implies criticism. If you want to sell me a biography then make it one that makes the subject look like a real person with both strengths and flaws.

On a particularly lighter note…I’m shocked that there is someone that reads this blog that has not actuall watched The Series, Move, and read the comics.

I watched it for the first time about two years ago. A late bloomer I suppose, but non the less have fallen in love with it like every other Brown Coat. The characters and plots are excellent and I just wish Joss would have been able to continue telling this story.

Point of reference: Right after I read this excerpt. I logged into Netflix and have been watching the TV series. For some reason it never gets old.

@6 You really need to “check it out” I hope you can watch and appreciate this show for what it is, Shiny!

@10, You make good points. Also, think back to the ONLY established mention of the needle, when Jubal Early infiltrated the ship, you see Inara open the box with the needle inside.

I don’t have too much a problem with the idea that the drug reacts to an indivual’s body chemistry, this is the future after all, that they could activate the drug through distress or even conscious thought. My concern is that SURELY some poor companion has been accused of murder, when her rapist died.

@10 Aeryl

The only time we saw the needle was in the pilot episode “Serenity” when the crew feared they might get hit by Reavers coming their way.

One of the few good things about Firefly’s cancellation is that Inara-raped-by-Reavers plotline never happened. Ditto the “Inara is dying of something” plotline.

So Fox thought the series was too dark yet they wanted Mal to kill someone every week? Yup, it’s never a dark moment when someone gets killed.

I think “Lodge’s Firefly Rant” beautifully sums up my feelings. And my brother-in-law kept asking for about three years “and they really won’t make another season?” after I got him hooked.

I never even found Firefly until after it was cancelled, and someone I met online sent me the episodes she’d taped. Later I bought the boxed set so I could see all the episodes.

I’m glad the Inara raped by Reavers episode never got made; the series was dark enough; it didn’t need that touch of brutality, but I like the idea of the needle…

@9 – “Women, especillay women like Inara who are engaged in work that is looked down upon”

I think you’re making the mistake of interpreting their behavior in the framework of 20th Century Earth.

In fact, Inara and Mal are citizens of a wholly different culture. In their ‘verse, Companions are well respected. In this context, Mal’s attitudes are odd in an entirely different way. He’s not being a misogynist, he’s just somebody with an unusual set of values.

Considering the recent revelation by Joss Whedon’s former wife that he had affairs with actresses he worked with, I wonder if an update of this biography is in order, with a whole different tone (this one seems to mostly compliment him and show him in a positive light).

@20. Agreed. I think it is time to take a good long and hard look at Whedon’s work in light of recent events. Not just his own self, but other external factors too. I mean, take Firefly; which Whedon has admitted he patterned our heroes on the South’s side. After Charlottesville, can we really accept something which is based on historical racists? Especially since Whedon has said he took the slavery bit out, which is exactly what the United Daughters of the Confederacy did with American South history when commissioning all their statues. Erasing slavery to make rebels seem noble is a major problem.

I also find it more that slightly concerning that while every other SF site on the web has had an article on the Whedon revelations, that Tor has steadfastly refused to even mention them. I know the Whedonbase runs strong here, but pretending that they haven’t happened is not a good look for Tor. Of course Tor regularly still promotes Marion Zimmer Bradley works, so….

@21 Generally speaking, rebels are worth making noble. I trust you don’t have a problem with the Rebel Alliance? Or the Bajorans for that matter.

While that’s not to say the Browncoats were only noble resistors against central authority, that they appear to have actually wanted only to be left alone by an encroaching authoritarian regime is a pretty big difference from the Confederacy. I used to be able to trust the issue would have been explored in further seasons of Firefly but Joss’ judgment seems increasingly suspect.

Give Me A Break.

Racism was a non issue in the ‘Verse. Classism on the other hand was rampant and at least one case of religious bigotry, the ship Barker who openly stated that Catholics weren’t welcome aboard. Slavery exists but is apparently extra legal.

If the Independence war was based on the Civil War the causes were flipped. The rebels were fighting for freedom and the Alliance for the power to enslave.

The problem is that Joss explicitly says that the Browncoats are based on Confederate rebels but erasing the slavery aspect. That promotion of that idea, that of the noble non-slavery rebel, is exactly what the United Daughters of the Confederacy wanted to encourage when they commissioned all the statues. Joss Whedon and FIrefly: heir to the Noble Confederate myth.

@24 Does that actually show up in the show? Not to mention the idea of the noble non-slaving rebel is also a construct from the War of Independence. If you erase slavery, the Confederate rebellion is indistinguishable from any number of more justifiable treasons.

Whatever Joss’ inspiration was, the reading you suggest means that any depiction of rebellion against heavy-handed central authority endorses the Lost Cause or Noble Confederate myths. I don’t think that’s a school of criticism we want to encourage.